Increasing your practice surface area

The difference between being good and being great isn’t talent or formal training, but the invisible practice that happens when you're just living life.

Budapest. Sometime around 1978. It's past 1am and all the lights in a high-rise apartment are out, except for one. A Hungarian girl — not yet 10 years old — sits on the cold bathroom floor balancing a chessboard on her knees.

Her father opens the door and finds her there, crying, "Sofia! Leave the pieces alone!"

The girl looks up at him. "Daddy," she says almost desperately, "they won't leave me alone!"

If you aren't familiar with this story, the girl is Sofia Polgar. In the years following the above scene in the bathroom, she'd go on to achieve one of the highest-performing ratings in chess history, playing for Hungary in four Chess Olympiads and winning two team gold medals, one team silver, three individual golds, and one individual bronze.

A lot has been written about the training regimen that Sofia went through with her two sisters: 5–6 hours of daily chess practice alongside studies in multiple languages and high-level mathematics in an apartment packed with thousands of chess books and detailed filing systems of their opponents' histories.

But not much has been written — how could it be? — about all the hidden reps Sofia got in outside of her official sessions. Like most elite performers, she had dissolved the boundaries of what counts as training and become high in something I call "practice surface area." It means what it sounds like: the total volume of time and space in your life where practice can happen.

The false dilemma of "talent vs training"

Let's say you and a friend decide to learn something new together. Guitar, chess, coding, whatever. You both sign up for the same class, practice for the same scheduled hour each day, watch the same YouTube tutorials.

Six weeks later, they’re proficient and you’re still stuttering through the basics.

We all know the standard explanation: talent. They’ve got it, you don’t. Some people are just wired for certain things. Better to cut your losses and find something that comes naturally to you.

Right?

Maybe! Usually what people mean when they call someone "talented" or a "natural" is that the person is genetically gifted. And genetics is real. But it's also not a very satisfying explanation because it's so nonspecific.

So if I may, I think what's actually taking place in most cases is a difference in practice surface area. You and your friend both officially practiced for the same "3 hours per week," but in reality your friend put in closer to 30. And they weren't even aware they were doing it.

They started hearing music differently. Every song on their commute became a lesson in chord progressions. Their fingers unconsciously worked through scales during meetings. They fell asleep running through the next day's session. They dreamed in tablature.

You began practicing guitar. They began living guitar.

High surface area is the rule, not the exception

I like studying world-class performers, and I can’t think of a single high-level pro who isn’t also high in practice surface area.

Take George Orwell. In his essay Why I Write, he reveals something that should have disqualified him from ever becoming a writer: he had a terrible time actually sitting down to write. The physical act of writing was torture for him. By his own admission, he would avoid it whenever possible.

So how did this writing-avoidant person become one of the most famous prose stylists of the 20th century?

Here’s the secret he buried in that same essay:

For fifteen years or more, I was carrying out a literary exercise of a quite different kind: this was the making up of a continuous “story” about myself, a sort of diary existing only in the mind… For minutes at a time this kind of thing would be running through my head: ‘He pushed the door open and entered the room. A yellow beam of sunlight, filtering through the muslin curtains, slanted on to the table, where a matchbox, half-open, lay beside the inkpot. With his right hand in his pocket he moved across to the window. Down in the street a tortoiseshell cat was chasing a dead leaf,’ etc. etc.

From childhood until age twenty-five, Orwell was practicing descriptive prose every waking moment. He wasn’t "writing," he was just existing lol. But his brain was secretly logging thousands of hours of narrative practice.

This pattern shows up everywhere once you know to look for it.

Richard Feynman didn’t become a legendary teacher by practicing lectures. He became one by explaining physics to imaginary students while walking around campus. He’d work through problems out loud in empty rooms, turning every moment of solitude into a teaching rehearsal.

Bobby Fischer carried a pocket chess set everywhere and would analyze positions using ceiling tiles as boards while lying in bed. Insomnia became chess study. Waiting rooms became tournaments. His opponents thought they were facing someone with supernatural talent. They were actually facing someone who’d turned every idle moment into chess.

In fact I've found so many examples of high practice surface area that I created a companion piece to this essay filled with nothing but examples.

Here it is: The hidden training habits of 21 world-class performers.

How to increase your surface area

It should go without saying that the best way to increase your practice surface area in a given field is to be obsessed with that field. Obsession makes quick work of formal and bounded training sessions, and it doesn't need "tips" on how to do so.

So the question then becomes, "How do I increase my practice surface area if I'm not already obsessed?"

I've got a few ideas:

1. Find the “minimum viable repetition”

Identify the smallest possible practice unit that requires no equipment, setup, or specific location.

Like Bobby Fischer analyzing chess positions on ceiling tiles while lying in bed, you need a version of practice so minimal it can happen anywhere, requiring zero setup or equipment.

2. Turn idle time into mental rehearsal

Waiting periods and dead time are great opportunities for visualization sessions where you mentally simulate perfect performance.

Michael Phelps would run “mental movies” of perfect races in waiting rooms and before sleep.

3. Embed practice into routine activities

Layer your craft directly onto daily activities.

Maya Angelou composed entire poems while mopping floors. She claims to have used the rhythm of physical work as a metronome for her words.

4. Create background processing systems

Develop automatic mental habits that keep your craft running in the background of consciousness throughout the day.

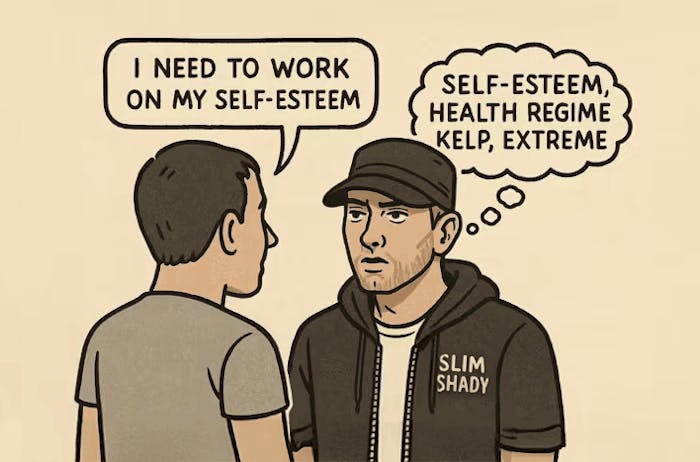

Eminem can’t turn off the part of his brain that rhymes everything. Every conversation, interview, even argument becomes inadvertent freestyle practice as he generates rhyme patterns for everything he hears.

5. Use environmental constraints as creative parameters

Convert physical limitations and situational constraints into practice parameters that force innovation.

The UFC fighter Anderson Silva would practice his striking combinations disguised as dancing at Brazilian clubs. He'd throw actual combat sequences to the rhythm while everyone thought he was just getting down.

Nice breakdown and generalization of a trend most people only know in language immersion being way more effective than years of narrow practice.

This concept of "practice surface area" is one of those ideas that seems obvious in hindsight but changes everything once you name it. The Polgar story is haunting—"they won't leave me alone" captures exactly what it feels like when your craft stops being something you do and becomes something you are.

Hello,

I’ve worked in Software development, and I’ve seen how small tweaks can make a big difference in both profitability and efficiency. I’d love to explore ways we can work together to streamline your work and help you reach your goals more effectively.

I am willing to pay you 20~30% of income in exchange for your support.

Are you open to a quick conversation to discuss this further?

Telegram: @justinguardian

This was really good.

The Sofia story is wild. That line, “they won’t leave me alone,” says everything about obsession.

I like the idea of practice surface area. It explains way more than just saying “talent.”

It also made me think about how many small moments I waste that could be reps.

All the examples resonate deeply but Richard Feynman is literally me.

i love this thanks for sharing

wow dude this was a solid post i would wait for your new update

Thanks! Plenty of new essays coming.

Mine is just money, I need to publish my website I am done, but I don't have $300 to do that

If you were starting today, what would you do differently in the first 90 days?

Love the "practice surface area" framing. It explains why some founders seem to progress 10x faster, they're not just building, they're living the problem. The Sofia Polgar exemple is perfect. She wasn't talented, she was unavoidably immersed. For indie hackers: talking to users in DMs, reading competitor reviews, noticing problems in your own workflows, that's all hidden practice, that doesn't feel like work.

Great insight. It shows how real growth comes from turning daily moments into practice. Mastery is built in quiet repetition, not just formal training.

Hi Indie Hackers Team,

I hope you're doing well. I’m interested in contributing high-quality articles related to technology, software, business, data science, and general scientific topics on Indie Hackers. My goal is to share valuable insights and practical knowledge with your community.

Could you please guide me on how to get a contributor or writer account to publish blog posts on your platform?

Thank you for your time and support. I look forward to your response.

Best regards,

Max

Mine is just money, I need to publish my website I am done, but I don't have $300 to do that

Wow, this was such a good read. The story about Sofia Polgar really pulled me in, crazy how something as simple as being obsessed can make all the difference.

The “practice surface area” idea makes so much sense. It’s not just about the hours we schedule, it’s about how much of our life we let it spill into. That part about Orwell practicing without even knowing it? So real. Makes me think I need to start paying more attention to the little moments that could count as practice too.

You touch a concept that's been, albeit indirectly, studied in the book Psycho-Cybernetics, by Maxwell Maltz. In that one, the writer mentions an experiment in which a basketball team is divided in 3 groups: one group shall practice only free shots for two weeks, one do nothing, and the third must not practice physically but must dedicate 5 minutes a day to "imagine" themselves doing free shots.

The results at the end where astonishing: while group two had no performance increase, group one and three improved it by almost the same amount (22% and 21%)!

I've read about that! The mind is so fascinating.

It really is! I've actually used that technique in some occasions and it does work surprisingly well.

Now if I could only visualize myself finding B2B customers to talk to, that would be great. Do you have any specific article on here you'd recommend reading? I'm just getting started and could use some guidance about the whole "find your users" thing 😅

This is a wonderful perspective.

The perspective that mastery is not simply about the number of hours you put into practice but about embedding mastery into your daily life, is powerful. It is truly about being absorbed in the practice, and allowing it to flow into your everyday life and your thinking. This perspective not only makes obtaining mastery easier, but it also connects the person to his or her craft in a greater way. It is an indication that every moment can be a moment of learning and growth.

Mine is just money, I need to publish my website I am done, but I don't have $300 to do that

Slim shady photo got me clicking

Glad to hear. Lots of people apparently don't know who he is and therefore didn't understand that image

This is a solid piece. Thanks for sharing your take.

Interesting takes here but I’m not sure I fully agree that “practice surface area” is always the key.

I’ve seen people surround themselves with a skill 24/7 and still make little progress — maybe because their actual practice wasn’t deliberate enough.

Like in sports, just shooting basketballs all day doesn’t make you Steph Curry.

It’s the combination of structured drills + all the hidden reps (thinking about plays, visualizing shots, analyzing games) that really compounds.

So maybe the formula is more like:

Formal practice (deliberate work) + Surface area (background reps) = Real growth.

Would love to hear how others balance this — do you lean more on structured practice or on ambient/hidden reps?

I actually agree with you, so I should've been more clear about the definition.

Surface area encompasses ALL practice. (Surface area = formal practice + background reps.)

This whole “practice surface area” concept really hit home for me.

I first noticed it when I was trying to learn a new language.

At first I thought 30 minutes of Duolingo or flashcards was enough. But progress was slow.

The real jump happened when I started surrounding myself with the language all the time — changing my phone to Spanish, listening to podcasts while cooking, even thinking in Spanish during random moments.

That’s when it stopped feeling like “practice” and

Yep, gotta immerse yourself in it.

I think “practice surface area” is something we often underestimate because it doesn’t feel like “work.”

I’ve seen it with coding too.

When I was building my first project, I used to only count the hours I was sitting in front of VS Code.

But then I realized I was solving bugs in the shower, thinking of UX flows while commuting, and even dreaming in code sometimes 😂.

Those hidden hours were probably worth more than the scheduled ones.

Love the idea of tracking this in some way — almost like a “second brain” log for invisible practice.

Has anyone here tried a method for capturing those small reps?

My intuition tells me the act of tracking informal practice would have a negative impact on it. I do lots and lots of personal tracking, and it makes you spend time/attention on overhead that you could be spending on the activity itself.

I love this idea, it is a great mindset to have.

Possibilities are in the eye of the beholder and I'm a firm believer. Mindset is everything!

Thank you so much for this sir, it is an eye opener and I really appreciate it.

Thanks for sharing the details. I'm still at the very beginning, so it's great to see what's possible.

I built an MVP to visualize ideas from text + images — where does it confuse you?

Reading this reminded me of how mastery really comes from the quiet, unseen hours. The idea of “practice surface area” makes so much sense it’s not just training time, it’s mindset. Interestingly, I came across a site aftcalculator(dot)io and it applies a similar principle in fitness focusing on consistent, small improvements that build real performance over time. Both this essay and that concept show how daily micro-practice creates long-term excellence.

Really liked the idea of “practice surface area.” It explains why consistency beats raw talent so often. I’ve noticed the same while building small utility tools — even tiny improvements made daily compound fast. Great perspective.

I like the idea of practicing surface area and i think that has to do a lot with the environment and people around you. If you are surrounded in a different environment, it's very much easier for people to simultaneously practicing/learning something without knowing it.

This was such an insightful read — reframing “talent vs training” as a matter of practice surface area really shifted how I think about skill growth.

The idea that you don’t just train during formal hours, but live the craft — letting idle moments become hidden reps — resonates deeply. It reminds me of how the best indie hackers don’t just build products in scheduled sprints, they think about them in the background, notice opportunities everywhere, and let their subconscious run practice loops even when they’re not consciously working. Indie Hackers

I especially liked the examples of habitual mental practice — it shows that consistent exposure and subconscious rehearsal matter just as much as deliberate work. Curious — how do you personally track or intentionally expand your practice surface area without turning it into structured “work time”? Indie Hackers

This really changes how you look at "talent". I've always wondered why some people just seem to pick things up faster, but it makes sense that they're just practicing in their heads all day. The Bobby Fischer example is a great way to visualize how that works.

Being good often comes from talent, or structured effort—things you can point to on a résumé. But being great comes from how you show up when nothing is being measured. It’s in the way you notice patterns while walking, how you listen during casual conversations, how you reflect after small failures, and how you connect ideas across unrelated moments.

This reframes “talent” in a powerful way — greatness comes from living the craft, not scheduling it. When practice spills into idle moments, progress compounds invisibly. High performers don’t train more intensely; they train more continuously.

Amplift’s creator filtering removes a lot of low quality accounts which is helpful. ( Amplift .ai)

Such a nice article, and i like the most is this one ( Develop automatic mental habits that keep your craft running in the background of consciousness throughout the day.)

Hello to everyone, i'm new here and I'm so greatful to be amongst you.

Thank you for these kindly contribution. These are so helpful in developing application.

such an incredible insights for management of situations.

@channingAllen.

Great insights, Channing ,this kind of thinking deserves way more reach.I do Reddit marketing for founders, and I help turn posts like this into real visibility and engagement across the right subreddits. If you ever want to amplify one of your essays or experiments on Reddit, I’d be happy to help you get it in front of the right people.

I really like the concept of 'practice surface area.' It explains why some people seem to accelerate so quickly they're essentially living inside the thing they're trying to master." makes me reconsider how I approach my own abilities, particularly the areas that I typically only "practice" within designated blocks.

nice

HOW I RETRIEVED MY BITCOIN WITH THE HELP OF/ THE HACK ANGELS RECOVERY EXPERT.

I just want to take this moment to appreciate the effort made by THE HACK ANGELS RECOVERY EXPERT and his team in recovering my scammed Bitcoin . Have you by any means invested your hard earned funds or Bitcoin with an Investment and later you find out you have been duped, and you would wish to track down and recover your funds. I am recommending them to everyone out there who have been defrauded too by these fake Bitcoin investment platforms. You can reach out to them with the information below: at

WhatsApp +1(520)200-2320)

They helped me when I thought I had nothing left to do.

This idea of “practice surface area” really resonates. I’ve applied something similar in my own work: taking years of consumer research on sleep and turning it into a tiny $2 product called The Tiny Sleep Method — a simple, science-based guide to help people improve sleep with small daily habits.

Appreciate the insight — it’s exactly the kind of thinking that shaped the product.

This beautifully captures what separates the good from the exceptional — not talent, but how deeply the craft seeps into every corner of life. ‘Practice surface area’ is such a powerful idea. It reframes mastery as less about scheduled effort and more about identity — when practice stops being something you do and becomes part of who you are. Love how the examples show that obsession isn’t about intensity, it’s about integration.

Such a smart way to look at learning. Makes me wanna ship and experiment more often 👀

This idea really clicked — treating every small action as practice turns ordinary moments into progress. It’s a refreshing, sustainable way to keep improving without burning out.

Really insightful read the idea of “practice surface area” perfectly captures how true mastery happens. It’s not just about scheduled effort but how deeply the skill becomes part of everyday life. Loved the examples of Sofia Polgar and Orwell great perspective.

This is such a powerful mental model. As builders, it's so easy to get stuck in 'theory mode'—endlessly planning, researching, and preparing to launch. This concept reframes action itself as the practice. Every small project, every failed MVP, every tweet, and every conversation here on IH is increasing our 'surface area' for luck, learning, and eventual success. It's a great antidote to perfectionism. Thanks for sharing this.

This is an insane deep dive into ‘practice surface area.’ The way you traced Sofia Polgar, Bobby Fischer, Orwell, Feynman, and Phelps — especially Fischer sneaking chess on ceiling tiles — perfectly illustrates how obsession converts idle moments into exponential skill growth.

hey! i can help if anyone needs a website! i read a lot of comments of people being lost or needing to finish a project quick and i can provide u with a website today for a negational price since not everyone can afford to pay 300dollars for a site. I will leave my fiverr here no need to pay that price just so you can contact me if u need it you can search Monk for website design and building and you should find it. Hope i can help anyone!

Nice post i would wait for your more update

Wow , this is such a powerful reflection on what real mastery looks like. I love the idea of “practice surface area” it perfectly captures how the best in any field blur the line between training and living. It’s not about doing more, it’s about making practice unavoidable.

This concept of 'practice surface area' really reframes how I think about skill-building. It’s not just about scheduled sessions; it’s about living your craft. The examples of Orwell and Fischer show how obsession turns everyday moments into compounding growth. Definitely bookmarking this one!

I absolutely love the concept of 'practice surface area.'

It clearly explains how "talent" is often just immersion—the difference between practicing an hour a day and living the craft 24/7. The examples of Orwell and Feynman using their mental downtime for 'invisible reps' are great proof.

Concise, actionable advice for true skill compounding. Excellent post!

Love this idea of increasing your practice surface area—it’s often the small everyday efforts that compound the most. I’ve found that trying lots of small side projects, sketching ideas, or experimenting with visuals (even basic ones) helps build confidence and skill without pressure. Thanks for sharing this—it’s a reminder to embrace imperfect practice.

First time encountering this concept, very insightful, thank you!

That’s a great way to frame it — “practice surface area.” It really comes down to creating more opportunities to fail safely and learn faster. Curious, what’s your favorite way to expand it — building new projects or improving old ones?

Great post — I really like the idea of “practice surface area.” It reminds me that so much growth happens in the tiny, hidden moments, not just during formal practice. Thanks for sharing this perspective!

Embedded practice is powerful. When something becomes part of how you live, it turns almost ‘free’ in mental cost — you’re training without draining yourself. How do you track whether these invisible reps are actually improving your skills? Feedback seems essential here — otherwise, you might just be repeating mistakes?

This is some really good stuff! I definitely agree with the concept of broadening the "practice surface area." The more we are in environments or situations where we are being challenged authentically in new ways, the better the opportunity for growth! For example, this could come from side projects, collaborating with or communicating with other people, or tinkering with new tools. The important part is to experiment – and make it a habit! Certainly, I have supportive evidence from my own experiences that have stemmed from doing things differently. I have, and still am pursuing some different methods of studying, and it is leading me to some incredible synergy outcomes, that I would have never imagined in the past. Not to divert from the post itself, but has anyone else ever intentionally stepped outside of their own comfort zone, and in turn, had significant growth from that experience?

Really like this idea of “increasing your practice surface area.” It’s such a practical way to think about growth not chasing perfection, just creating more opportunities to learn by doing. It’s amazing how consistent small reps compound over time. Thanks for sharing this!

If you’re trying to stay focused while working or studying, you should try Mixora — it’s a free focus web app where you can set timers (15, 25, or 50 mins), track streaks, and even create Spotify playlists based on your mood or favorite artists. 🎧

It also has relaxing background sounds like rain, café, or forest that you can customize.

Super simple, no signup needed → mixora . xyz

That’s such a fascinating read — it really shows how greatness often comes from those invisible hours of practice that most people never notice. It reminds me of how some gamers approach Stick War Legacy, constantly improving their strategies even outside of gameplay.

This is such a powerful perspective

I’ve noticed the same thing in my own work — the real difference often comes from all the "invisible reps" you put in outside of official sessions.

For example, I recently started experimenting with building niche content sites.

Even though I was only doing 1–2 hours of “scheduled SEO work” per day, I realized my brain kept running in the background — analyzing keywords while browsing, noticing competitors’ site structures, thinking about backlinks during idle time.

That hidden practice surface area has actually helped me grow one of my projects much faster than I expected.

Curious — how do you personally notice and track these “invisible practice hours”? Do you just let them happen or do you have a system for it?

Great point! I’ve noticed the same phenomenon building my UX audit tool—the “background processing” of user flows while doing unrelated tasks often sparks the best ideas. I’m curious how to deliberately expand that practice surface area without burning out. Do you have any tactics for turning everyday experiences into productive reps without obsessing over work 24/7?

Really like this frame: make good reps cheap, frequent, and visible so practice compounds without drama. What’s worked for me is shrinking the unit of work (15-min drills), defaulting to public artifacts (tiny write-ups, screenshots), and setting “always-on” cues (same hour, same place, same playlist) so momentum doesn’t depend on willpower.

Curious tho, of the levers you tried, which moved the needle most: smaller scopes, public streaks/accountability, or environment design that removes friction?

P.S. I’m with Buzz; we build conversion-focused Webflow sites and pragmatic SEO for product launches. Happy to share a quick 10-point GTM checklist if useful.

hi HN

Reading this reminded me of how mastery really comes from the quiet, unseen hours. The idea of “practice surface area” makes so much sense it’s not just training time, it’s mindset. Interestingly, I came across a site aftcalculator(dot)io and it applies a similar principle in fitness focusing on consistent, small improvements that build real performance over time. Both this essay and that concept show how daily micro-practice creates long-term excellence.

This is an insane deep dive into “practice surface area.” The way you traced Sofia Polgar, Bobby Fischer, Orwell, Feynman, and Phelps — especially Fischer sneaking chess on ceiling tiles — perfectly illustrates how obsession converts idle moments into exponential skill growth.

I love how you:

1. Highlighted Sofia’s informal reps outside structured practice, proving skill isn’t just scheduled hours.

2. Tied it to universal mental rehearsal, showing Orwell and Phelps’ invisible training.

3. Made the concept actionable with those 5 steps — especially the “minimum viable repetition” and embedding craft into routine activities.

Takeaway for anyone trying to level up: obsession + practice surface area > conventional grind. Even if your formal sessions are short, your brain can compound skills all day.

From a professional strategic lens: this principle is pure gold for founders and creators. For example, in promotional email copywriting, “practice surface area” could be tiny daily tests: analyzing micro-open-rate shifts, tweaking subject lines during downtime, or mentally rehearsing CTA phrasing — all invisible training that compounds into high-converting copy. Applying this can literally multiply LTV and reduce churn.

Here’s a small actionable tweak that could push this essay even further: add a mini-framework for readers to start creating their own practice surface area today — e.g., “3 Micro Reps per Idle Hour” with examples tailored to their field. This makes the concept immediately actionable and sticky.

If you want, I can map out a 1-week mental rehearsal routine for founders or creatives to embed obsession-driven micro-reps into their workflow, using the same principles as Fischer’s ceiling-tile chess strategy. DM me “Surface Area” and I’ll drop it — it’s free, high-value, and actionable enough to show measurable skill compounding.

I just opened my Fiverr gig for my Systeme io / ClickFunnels funnel service — I’m offering 50% off my first few clients to collect reviews. How to reach me +18582509952

This comment was deleted 3 months ago