From open-source donations to $13k MRR product

Andris Reinman is the creator of Nodemailer, an open-source project used by hundreds of thousands of developers. But it didn't pay the bills. So he launched related open-source product — EmailEngine — and transitioned it into a $13k MRR business.

Here's Andris on how he did it. 👇

From open source to SaaS(ish)

I’m an email software developer and open-source maintainer. I’m best known for my open-source work — most notably Nodemailer, which is used by hundreds of thousands of developers and companies worldwide.

While open source brings a lot of visibility and impact, it doesn’t really pay the bills. I do receive regular donations, but they’re in the low hundreds per month.

About five years ago, I decided to turn my experience in email infrastructure into a business and started a company that builds and sells email software.

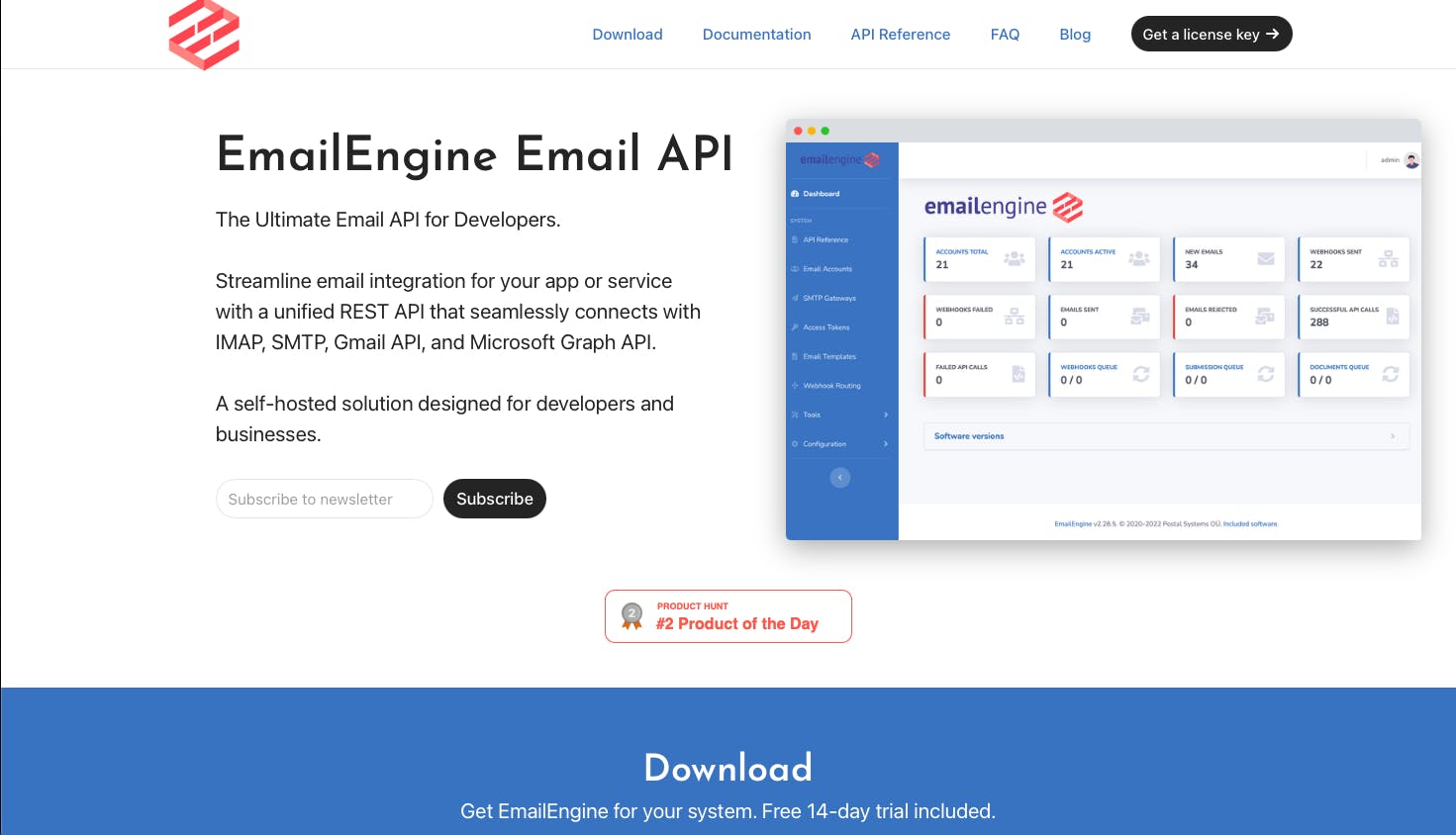

The original plan was to build multiple products, but in practice, one clearly stood out. Since then, I’ve been focused almost exclusively on EmailEngine — a self-hosted application that lets developers access email accounts via a simple HTTP REST API instead of dealing directly with IMAP, SMTP, or vendor-specific APIs like Microsoft Graph or Gmail.

We're currently at $13k MRR, growing at roughly 20% per year. Revenue growth has been slow but steady, so the revenue chart has no sudden bumps or exponential curves — just a mostly linear line from zero to its current position.

Burning out and starting up calmly

I was the CTO of a small VC-funded startup for four years. I took my laptop to the toilet and put it under my pillow while sleeping, just in case something happened and required a fast reaction. After four years, I was burnt out. I wanted a break.

As a long-time developer, taking a break still meant working — just without the pressure. That mindset shaped many of my decisions later. It’s also why I don’t provide managed hosting or take on large customers. If someone contacts me asking for a demo or wants to negotiate with “my sales team,” I kindly point them to some of my competitors instead.

All my customers are self-serve — usually competent, small technical teams that don’t require hand holding and therefore don’t burden me with constant support requests. What was originally meant to be a short break until I ran out of cash reserves turned out to be a viable business. I’ve been doing it ever since.

An unusual tech stack

EmailEngine is built on Node.js and uses Redis as its database. The homepage is hosted on umso.com, and the documentation is a Docusaurus project hosted on GitHub Pages. I also use Claude Code a lot these days.

Using Redis as the main database is not a very common choice — Redis is usually seen as a caching layer rather than an actual database. In my case, Redis was the option that had the best compatibility with IMAP indexing, specifically because of its Sorted Set data structure. Without going too deep into the details, that was the deciding factor.

I also didn’t want to ask users to set up multiple databases for different purposes, so I decided to use Redis for everything. It’s a choice I’ve sometimes regretted. Redis is missing a lot of features you’d normally expect from a database, like proper querying, and that has meant spending time implementing workarounds I wouldn’t have needed with a more traditional DB.

That said, keeping things simple has helped overall. It’s much easier for users to spin up their first trial instance for testing, and once someone is already testing the product, they’re much more likely to start paying.

Technical challenges

EmailEngine is technically a complex piece of software, and the main challenge has been that every customer uses it slightly differently and against different email backends. Even though email protocols have been standards for a long time, there are still noticeable differences between providers. What works one way with a Gmail account might behave differently with, for example, Korean Naver mail hosting.

These issues are hard to plan for in advance. If I don’t have an account with a specific email provider, there’s no real way to test it. Getting access to such accounts can be expensive if the provider is commercial, or outright impossible in some cases — especially with regional providers that require a local mobile number for account verification.

Finding the model

EmailEngine started out as yet another open-source side project, so for the first two years, I worked on it in my free time while still at my previous job. Initially, I didn’t intend it to become an actual business. The idea was to use it to increase the donations I was getting for supporting my open-source software development.

That didn’t really work, so I tried a dual-licensing approach. The open-source version was licensed under AGPL, and for “serious businesses” I offered an MIT-licensed version for a small yearly fee. There were almost no takers for that either. This phase took about a year and a half.

Eventually, I decided to go fully commercial, and almost immediately started gaining customers — mostly previous users of the free project, but also companies that wanted continued updates and upgrades.

So now, it is self-hosted software that requires a paid subscription to operate. Without a subscription, it runs in a 14-day free trial mode, after which it stops working. Subscriptions are yearly and self-renewing, and I use Stripe for subscription management. There is only a single subscription plan. There are no upsells or tiers — everyone gets exactly the same product, whether they’re a solo developer or a large bank.

Since there’s no hosted or managed version, I don’t really consider it SaaS — more like on-prem software with a subscription model.

After monetizing it, it remained a side project that I worked on during evenings and weekends. But I was already burned out from my day job. I started the process of exiting that role, which, for various reasons, took about half a year, until I was finally able to go all in.

At that point, EmailEngine was still not making enough to support me financially — around $500 MRR. I was living off my previous cash reserves, but I could see the potential and, more importantly, I actually wanted to work on this project. So I went all in and started working on it full-time.

Growth via open source projects

The biggest obstacle was reaching a point where the revenue was high enough for me to start paying myself, so the project no longer felt like a temporary pet project. But it wasn’t something I had to actively “overcome” in a deliberate way. At first, the revenue simply wasn’t enough. Over time, it became enough.

I didn’t push for growth. I just kept developing the product, saw that there was steady growth, and assumed that eventually it would get there — and it did.

The first ~10 subscribers were all users of EmailEngine back when it was still an open-source project. At the time, it had a different name - IMAP API. IMAP API was fairly popular, with around 1,000 stars on GitHub.

Otherwise, I’ve used a single growth “strategy” from the beginning. I’d call it engineering-led marketing. I’ve released a number of popular open-source and free products, and linked from those to EmailEngine.

Since all of these projects are email-related, there’s a natural overlap. For example, a Nodemailer user might eventually need features that Nodemailer doesn’t provide, but EmailEngine does — such as Microsoft Graph API–based sending using OAuth2. In those cases, they may end up checking out EmailEngine, and in rare cases, they end up paying for it.

I’ve never done paid ads — my marketing budget has always been $0.

The only other approach worth mentioning has been SEO. In particular, the “EmailEngine vs. some major alternative” type of articles. Users of those alternative providers who aren’t happy with their service go looking for options, find EmailEngine, and some of them turn into customers.

That said, it likely works both ways. I don’t really know whether I’ve gained more customers than I’ve lost to competitors through this, but overall it seems to have worked well enough.

The advantage of experience

My background in building open-source email projects has been a big advantage. Over the years—Nodemailer is 15 years old by now—I’ve gained fairly rare experience in a topic that is both complex and boring for most people. Along the way, I’ve also built an audience of developers who already use my projects.

Labeling EmailEngine as “made by the creator of Nodemailer” definitely makes it more trustworthy. Nodemailer has been around “forever” and quietly does its thing, so people tend to assume EmailEngine will probably do the same.

Look for your edge

Here's my advice: Look for an edge you might have — one that either you haven't noticed yet or you don't think of as an edge.

For example, I never considered my open-source work to be a growth driver for a business. It only turned into one after I had already started.

What's next?

I plan to keep building EmailEngine, and maybe return to my original idea of building multiple related projects. I’ve had many ideas over the years, but haven’t had the time — EmailEngine has been large enough to require my full attention.

Now, with AI, software development has become much faster, so I might revisit some of those old ideas. For example, a purely email-sending–oriented solution that would be much more scalable than EmailEngine — essentially providing the same email-sending capabilities, but in a more scalable way.

EmailEngine is tightly coupled to individual email accounts, and since each account requires constant attention — polling for new messages or accessing the mailbox — it consumes a lot of system resources. There’s also no horizontal scaling, which makes it difficult to build large-scale sending solutions on top of it.

As far as revenue, I have no plans to increase it beyond its current trajectory. As a solo business with essentially no cost base, and living in Eastern Europe, I’m quite happy with the current state.

You can follow along on LinkedIn. Here's the EmailEngine landing page, documentation, and source code. Note: EmailEngine is not open source but source-available: anyone can inspect the full source code, but using it requires a valid subscription.

Leave a Comment

Thanks for sharing your story. The 'looking for your edge' advice is thought provoking, because you imply that it is often a blind spot. I wonder if it would be useful to build a taxonomy of skill categories - with such an artifact, it might be in interesting artifact to help identify one's own edge, as well as to consider where AI might be able to help you with areas that you don't have an edge, but which are important to attend to. Hmm 🤔